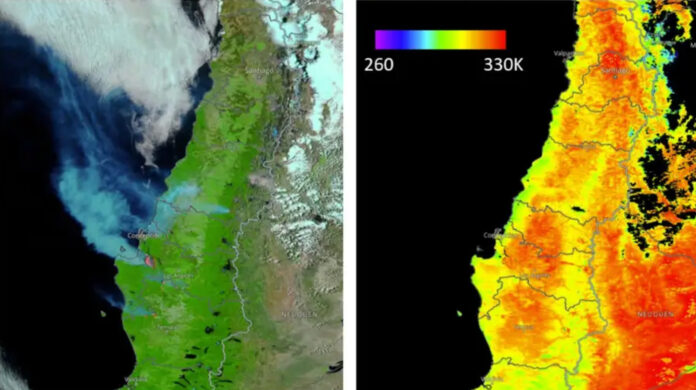

Fires in central and southern Chile, exacerbated by extreme temperatures and megadrought, have led to at least 26 deaths and burned more than 2700 square kilometres

By James Dinneen

Forest fires burning in central and southern Chile have led to at least 26 deaths and nearly 2000 injuries in what is among the deadliest wildfires on record in the country.

The fires have burned across more than 2700 square kilometres as of 7 February, according to a release from the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. More than 1000 homes have been destroyed and 280 fires were still active as of 6 February, according to Chile’s disaster response agency SENAPRED.

Already, that makes this the country’s second-most destructive fire season on record after 2017, which saw thousands of fires burn more than 5700 square kilometres and led to at least 11 deaths. Most forest fires in Chile burn in January and February at the height of the southern hemisphere’s summer.

More than 6000 Chilean firefighters have participated in battling the blazes. Brigades from Spain, Mexico and Argentina are also helping to fight the fires, along with more than 70 planes and helicopters.

Extreme temperatures and years of drought have contributed to the scale and intensity of the fires.

Weather stations in Chile’s Central valley reported record or near record temperatures above 40°C (104°F) over the weekend, says René Garreaud at the University of Chile in Santiago. High temperatures and strong winds are forecast for the coming days. “Meteorology plays against us,” he says.

Garreaud says the extremely high temperatures are driven by warm, naturally recurring “Puelche winds” blowing from the east, superimposed on a warmer climate. The past decade has been the warmest on record in Chile, says Garreaud. Megadrought in the region – the past 10 years were the driest on record in Chile – has also contributed to fires, he says.

The fires have mainly affected the regions of Maule, Ñuble, Bío-Bío and Araucanía, which together contain most of Chile’s forest plantations. Along with heat and drought, the added fuel load from the plantation trees have also increased the area at risk of fire.

Mark Parrington at the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Services said the fire’s intensity is reflected by the huge plumes of smoke sent billowing over the Pacific Ocean. The service estimates the fires have so far released 4 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, leading to the highest emissions from some regions in the past 20 years.

Original publication from New Scientist