In Chile, water is considered a national good for public use and usage rights are granted to private individuals, who as titleholders can use, enjoy, and have access to water, according to the current legal framework.

Research centred on a river in the Maule Region found that under the current system more water rights have been granted than there is water available in the basin; that the quality and availability of information is deficient; and that the variability in water availability under the changing climate has been underestimated.

By Pilar Barría, Maisa Rojas, Pilar Moraga, Ariel Muñoz, Deniz Bozkurt, and Camila Alvarez-Garretón.

Chile’s current water crisis is unfolding in a market-based legal context, in which water rights (Derechos de Agua, DAA) are owned by private parties. From this perspective, a study published (in Spanish) in the journal Elementa based on a case study of the water rights granted for the River Perquilauquén in the Maule Region questions whether this system is consistent with the biophysical realities and streamflow variability in Chile’s river basins.

The study analyzed (a) observed precipitation and water flow data for the River Perquilauquén from 1963 to 2015; (b) a reconstruction of streamflow data for the period 1590 to 2000, based on tree growth rings; (c) the projected streamflow regime for the 2006 to 2098 period; and (d) available information on water rights in the basin.

One of the first conclusions was that the quality and availability of data on the granting of water rights is deficient. Furthermore, water rights are not granted in a standardized magnitude, with some issued in litres per second and others in shares, but no equivalent volume is defined by the Water Authority (Dirección General de Aguas, DGA).

Assuming that the information available on water rights is complete, the main finding of the research was that the water rights for the River Perquilauquén have been over-allocated. This means that more water has been granted for monthly use than is available in the basin, which is a significant concern, as although in practice not all the water granted is actually used, there are no limits on its extraction and neither is there enough volume to meet all authorized usage.

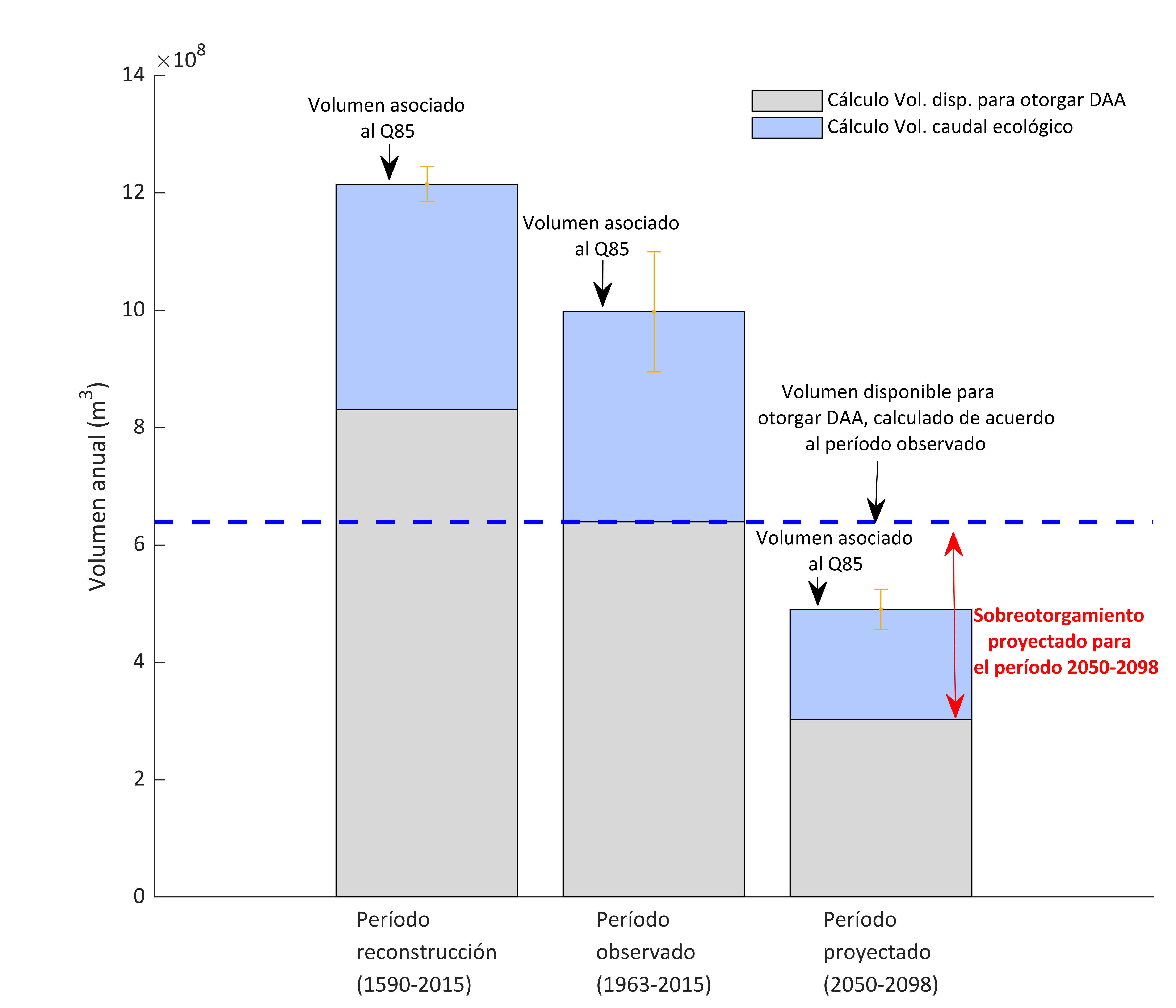

Lastly, the study concluded that the system does not take into account the variability of streamflow through the basin that is caused by changes in the climate. This result was arrived at by comparing the reconstructed streamflow data (1590-2000) with the observed flow (1963-2015), and projected flow (2006-2098). The data indicate that streamflow has been diminishing over time and will drop even more in the future under the climate change scenario and the occurrence of events such as the megadrought that has prevailed since 2010. This conflicts with the current method for assigning water rights (see Figure) and estimating water availability, which assumes that the availability of water in the basin is stable or fixed; in other words, the basin is responding to the climate in the same way it has done as far back as the records stretch. Because streamflow observation records go back a relatively short time in Chile, the assignment of water rights has overestimated the current and future availability of water, leading to the potential over-allocation of this resource.

Considering that what this case study has documented for Perquilauquén could also apply to other areas of the country, the authors recommend revising the methodology currently used to grant water rights, incorporating the fact that both the climate and the hydrological response of Chile’s river basins will change over time. This will enable better distribution of water resources, safeguard ecological flows, and maintain the ecosystem services that these provide. The study concluded that significant changes to Chile’s water management are needed to take into account the country’s environmental needs, the current water shortage, and the climate change projections for the future that may lead to water flows that are neither fixed nor constant.

Figure: The volume available for permanent water rights within a basin is calculated as the annual volume that is exceeded 85% of the time (Q85), minus the ecological flow. The figure illustrates how this available volume varies, depending on the estimated Q85, and how in the second half of the 21st century, rights granted in perpetuity within the basin surpass the volume that is theoretically available.

Figure: The volume available for permanent water rights within a basin is calculated as the annual volume that is exceeded 85% of the time (Q85), minus the ecological flow. The figure illustrates how this available volume varies, depending on the estimated Q85, and how in the second half of the 21st century, rights granted in perpetuity within the basin surpass the volume that is theoretically available.