By René Garreaud & Deniz Bozkurt | Edited by José Barraza | 30 July 2020

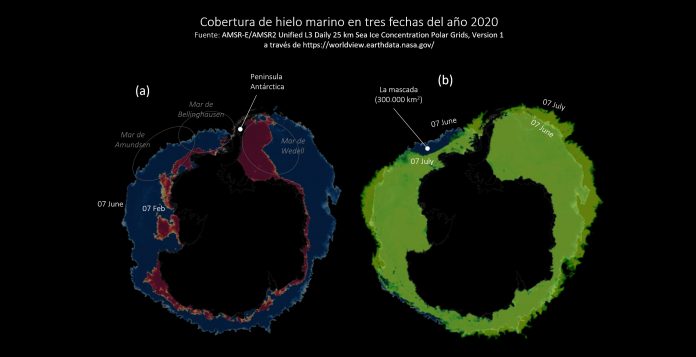

The seasons in Antarctica are unmistakable. In summer, the ice and snow are concentrated on the mainland, although even in this season an ice shelf (Figure 1a) extends out into the Weddell Sea east of the Antarctic Peninsula. As autumn advances, followed by winter, the ice covers over the rest of the ocean surrounding the continent. In early June this year, for example, the sea ice extended out 900 kilometres into the Bellinghausen and Amundsen seas west of the peninsula (Figures 1a-b). A month later, on 7 July this year, the sea ice continued to advance (Figure 1b) as usual…except for noticeably retreating on the Bellinghausen and Amundsen seas. This ‘bite’ left some 300,000 square kilometres of the Southern Ocean ice-free, an area similar in size to that between the Coquimbo and Los Ríos regions in Chile!

Figure 1: Panel a (left) shows ice coverage (in red) on the Weddell Sea on 7 February 2020. Panel b (right) shows sea ice (in green) on 7 July 2020. In both figures, the blue indicates sea ice coverage on the Bellinghausen and Amundsen seas in early June 2020.

Figure 1: Panel a (left) shows ice coverage (in red) on the Weddell Sea on 7 February 2020. Panel b (right) shows sea ice (in green) on 7 July 2020. In both figures, the blue indicates sea ice coverage on the Bellinghausen and Amundsen seas in early June 2020.

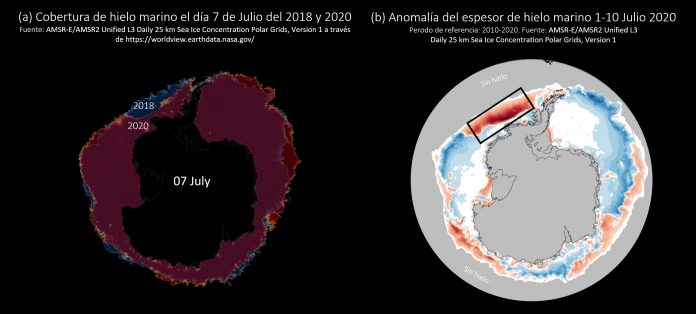

Does the ‘bite’ occur every year? Not at all. Figure 2a compares sea ice coverage on 7 July this year against coverage on the same day in 2018, by way of example. In this case, we estimate a difference of close to 500 square kilometres of sea ice between the two years. Furthermore, Figure 2b shows the difference in sea ice thickness in early 2020 compared to the average over the past ten years. These preliminary findings indicate that sea ice coverage west of the peninsula this year is the lowest in recent decades. The consequences for the cryosphere and marine environment could be equally significant.

Figure 2: Panel a (left) compares the coverage of sea ice on 7 July 2020 (in red) to coverage on 7 July 2018 (in blue). Panel b (right) shows the difference in sea ice thickness at the beginning of this year in relation to the past ten years.

Figure 2: Panel a (left) compares the coverage of sea ice on 7 July 2020 (in red) to coverage on 7 July 2018 (in blue). Panel b (right) shows the difference in sea ice thickness at the beginning of this year in relation to the past ten years.

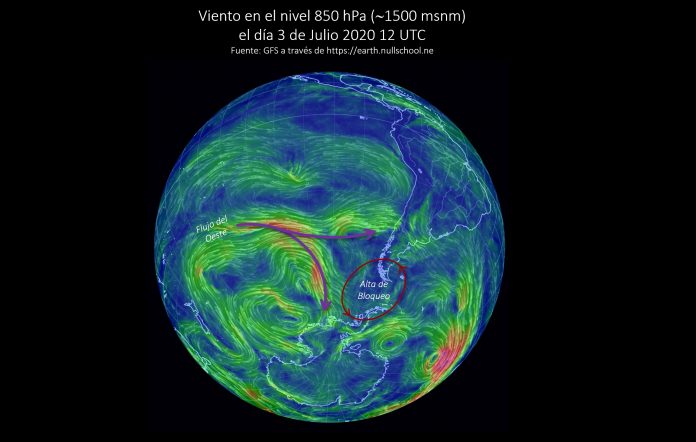

It is also important to explore the origin of this hole in the sea ice, to separate the effect of climate change from that of natural variability. In the immediate term, we have observed that from mid-June to early July, atmospheric circulation at high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere was intensely perturbed by a persistent high pressure zone centred over the Drake Passage, which acted as a blockage to the western flow that usually predominates in the area. Figure 3, for example, shows clearly how the westerly winds bifurcate into two plumes, one flowing towards south-central Chile (causing rain in that area) and the other directed precisely towards the Amundsen/Bellinghausen area. The latter plume is responsible for transporting relatively warm, moist air, occasionally organized into intense Atmospheric Rivers (AR), to the periphery of Antarctica. The presence of these air masses from lower latitudes in the South Pacific probably contributes to the melting of sea ice by increasing sensible heat flux to the surface and reducing radiation loss from it.

Figure 3: The red circle denotes a high pressure zone that effectively blocks the western flow, causing a bifurcation (purple arrows), with one plume flowing to south-central Chile and the other towards the Amundsen/Bellinghausen area.

Figure 3: The red circle denotes a high pressure zone that effectively blocks the western flow, causing a bifurcation (purple arrows), with one plume flowing to south-central Chile and the other towards the Amundsen/Bellinghausen area.

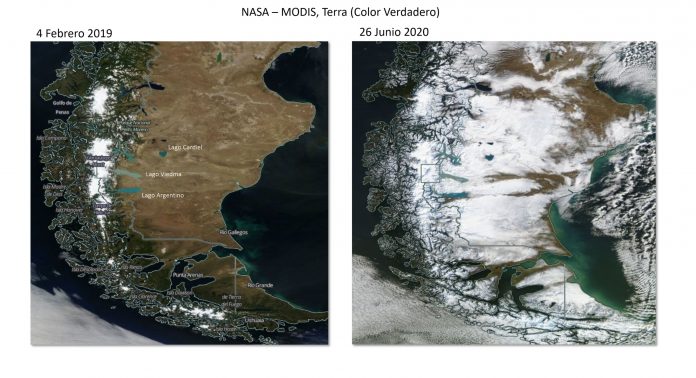

And the final surprise: the anticyclone blockage south of the continent was responsible for keeping Patagonia frozen for several weeks, providing a clear, white view of the region (Figure 4, see also: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/146946/rare-peek-at-patagonia-in-winter) and even of the strong winds blowing down from the southern Andes in the east to the channels of Patagonia. Those winds contributed to an accident at a fish farm on 27 June of this year that could potentially have adverse effects on the environment in the fjords and channels of southern Chile.

Figure 4: Comparative view of Patagonia on 4 February 2019 and 26 June 2020, two exceptionally clear days in the southern cone of South America with a very high thermal contrast. The image from February 2019 coincided with a heatwave that contributed to a huge forest fire in the Aysén Region (http://www.cr2.cl/analisis-incendios-en-aysen-cr2/). The image from June of this year shows ice and snow covering the continent from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic coast.

Figure 4: Comparative view of Patagonia on 4 February 2019 and 26 June 2020, two exceptionally clear days in the southern cone of South America with a very high thermal contrast. The image from February 2019 coincided with a heatwave that contributed to a huge forest fire in the Aysén Region (http://www.cr2.cl/analisis-incendios-en-aysen-cr2/). The image from June of this year shows ice and snow covering the continent from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic coast.